Is reality catching up with investors' favourite narratives?

Update: George Pearkes from Bespoke and Brad Setser picked up on the debate on border adjustment tax here. Some important perspectives.

--

I am still willing to give Mr. Trump the benefit of the doubt. We have no actual policymaking to judge yet, and at least some of the people he is surrounding himself with look capable. I admit, however, that the burden of evidence is getting heavy. The president-elect's tweets, on their own, are evidence that he has tendency to act long before thinking. Last week's presser also provided a timely reminder that we are dealing with a volatile character. I understand that infuriating "soft" liberals, such as yours truly, is exactly what Mr. Trump and his strategists want. I have no doubt that the incoming administration's communication "style" is carefully planned. The base loves it! But problems are brewing, chiefly among which is the growing chasm between Mr. Trump and the intelligence apparatus upon which he will so desperately depend for policymaking when he takes office. I have no clue about the veracity of the proposed leak, and who pushed it in front of us. But a U.S. president fighting with his two main intelligence services over allegations that the Russians have a pinch on him points to a weak and disjointed executive. No one benefits from a weak presidency in the U.S., and I am increasingly worried that is what we'll get.

Have markets run ahead of the inflation trade?

Having to spend so much energy on the incoming U.S. president is undoubtedly frustrating for investors, but it's their own fault. When the results first came in, their initial reaction was to punch the ticket forcing Spoos limit down. Since, however, it has been all milk and honey, reflation and Trumponomics. I have no problem with punters using politics as a catalyst, but don't come crying when it blows up in your face. Leftback, who recently returned to his proper place above the fold at Macro Man, does an excellent job synthesising the story.

According to this strong dollar, reflationary view, one should therefore sell vanilla Treasuries and longer duration debt, and buy high yield bonds or TIPS. In equities, one should sell defensive sectors, such as utilities, REITs, health care and staples, avoid other rate-sensitive issues such as telecoms and technology and buy the cyclical sectors, such as the financials, materials, integrated oil stocks, the drillers and industrials. This is the traditional recovery investment playbook (think about 2009, for example).

He then goes on to debunk the story in a convincing fashion. You really ought to read the whole thing. I suspect Leftback is making a more fundamental point on the reflation trade than I am. But in the short run at least, I completely agree. The macro data never tell a perfectly coherent story, but if we look at the numbers relative to expectations, the message is clear. The chart below shows that macroeconomic surprise indices in all the major economic regions have surged. This is consistent, I think, with the idea that markets have taken the reflation trade a bit too far. If economic data start to surprise to the downside, it probably would curb investors' enthusiasm.

All aboard for the great reflation?

As for the actual macro data, I struggle to get excited about the notion a strong and sustained acceleration in growth given the overwhelming evidence that the business cycle is long in the tooth, at least in the U.S. and Europe. Headline leading indicators aren't exactly screaming higher growth either.

An excessively pessimistic picture?

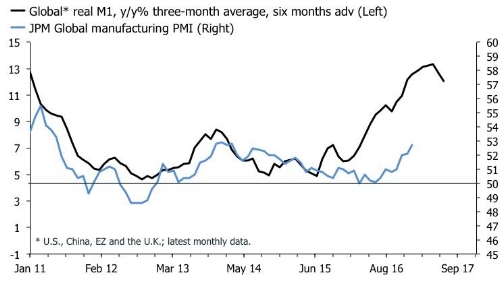

For the sake of counter argument, though, the rather depressing message from the chart above doesn't gel with the story we're telling at Pantheon Macroeconomics where it is our day job to keep a very close eye on the economic data. This is to say that if the economic cycles in the U.S. and the Eurozone are indeed in their later stages, we haven't yet seen any signs in the hard data, let alone the main business and consumer sentiment surveys. Further to this point, the upturn in global manufacturing activity appears to have legs.

Is the upturn in global manufacturing real?

The main implication of the chart above is that hard economic data such as industrial production, new orders and exports/imports of manufacturing goods likely will continue to come in strongly, and even accelerate in the short run. In addition, lagging indicators such as CPI and PPI almost certainly will continue to surge in the next three months.

Hanging on to the reflation trade

Investors have by and large clung to the reflation trade in the first sessions of 2017, but signs of slower momentum has emerged. The relentless rise in bond yields has been halted, and equities also have moved sideways if not weakened slightly. The notable exception is the FTSE 100 which taken shorts—of which I unfortunately am one of them—for a proper ride.

A couple of weeks ago I laid out a similar argument as LB does above, identifying defensive equity sectors and government bonds as best opportunities at the beginning of 2017. I see no reason to change that view, even if the president-elect decided to kick my number one sector healthcare in the groin this week. He accused them of "murder" and promised legislation to curb their pricing power. Well, it is getting difficult to mention a part of the economy and market which hasn't been Trumped, so I am not convinced that we should worry that much.

Most of my strategic indicators suggest that investors are best served by accumulating exposure in fixed income relative to equities, and that defensive sectors are likely to outperform cyclicals in the next three-to-six months.

The first chart below shows my forward looking valuation score for the MSCI World, and the second shows a similar model for U.S. 10-year equity futures. The message from this simple framework is clear for strategic asset allocators. Now is the time to accumulate fixed income and sell/avoid equities. I think this point is valid regardless of whether you think the new U.S. administration will manage to kickstart the economy in earnest.

The question of "political uncertainty" is another theme which has vexed investors in the past six months. We seem to have an awful lot of it, but financial markets and the economy have so far been oblivious to the changing political winds. The chart below, which suggests equity volatility is horribly mis-priced, is often shown as an example of this conundrum, but there are many other variants.

My personal bias wants the chart above to be true, but I am not sure that it means what equity bears think it means. After all, political polls were spectacularly wrong last year, so couldn't measures of political uncertainty be wrong too? If I look beyond my personal views of the changing political landscape, I end up with the frustrating conclusion that we don't know what exactly Mr. Trump can and will do—last week's pressed gave no new information—and we also don't know what Brexit will look like.

On the latter, however, things are stirring. Reports suggest that Theresa May will use a speech on Tuesday to announce her intention to push for a clean, quick and hard exit from the EU. I reckon this is just about as good as Mrs. May can do with the hand she has been dealt. We all know that the starting point of these negotiations won't be the final destination. A hard Brexit, however, has a number of advantages. It delivers on the mandate of the referendum, and will appease the hardliners in the Tory party. In addition, it makes things rather easy for the EU too. I don't think Mrs. May will face much from opposition Brussels if she indeed goes for a quick exit from the EU. The remaining EU countries have enough on their plate, and I think they are increasingly of the position that a quick Brexit is the best for all parties involved.

The main downside is that the economic benefits accruing from the tight trading relationship between the U.K. and the major EZ economies could be kicked into reverse. The cost will be lower growth in both regions. In addition, a hard Brexit will accentuate the uncertainty for the millions of EU nationals currently in the U.K. and the U.K. citizens living and working on the continent. It's a sad state of affairs really. But many EU nationals who have lived in the U.K. for decades will be asked to leave under the new rules. Even with the best of intentions and guarantees a lot of people will fall through the cracks when the new system is put in place. We must remember the reality, though. The referendum in part was a rejection of the rights of EU nationals to live and work in the U.K. as part of the freedom of movement enshrined in the Single Market. We are deluding ourselves if we argue otherwise. A big chunk of the U.K. populace would rather see the backs than the fronts of their EU brethren. We may think this is harsh—personally I think it is a tragedy—but it is the U.K. population's democratic right to make this choice.

As an EU national in the U.K. I am reconciled with the idea that I might be kicked out. But I reckon that my current taxes and NI contributions will be enough to grant me a pass, if I want to stay. After six years here, I actually have a lot of respect for the rugged island dwellers. They'll manage just fine. But they have a problem now. They have steered themselves into a cul-de-sac. Clamping down on immigration must now go hand-in-hand with the ambition to re-invent the country as a swashbuckling free-trading nation no longer held back by the shackles of the EU. It is a now country that presumably will do a free trade deal with anyone, or even rebrand itself as a tax haven, to prove that point. I am not sure how these stories can be reconciled, nor whether the actions to sustain them will do the economy any good. All the while, the U.K. economy borrows heavily—it runs a twin deficit of almost 10% of GDP—to sustain growth. Make no mistake about this. Closing a twin deficit of this magnitude quickly and disorderly would do a lot of harm to the weakest members of the U.K. society. This last bit is also why markets will be watching Cable on Tuesday as Mrs. May goes to the podium. A re-test of the flash crash lows could well be in the cards.

Remember the strong dollar story?

A lurch lower in the GBP would provide a little comfort for the dollar bulls who have had a stuttering start to the year. The dollar-bull story and reflation stories effectively are equivalent. So signs that the former is fading suggest downside risk to the latter too, consistent with the evidence presented above. It isn't completely clear to me, though, that the macroeconomic story has changed, but as with so many other themes derived from the U.S. president-elect's promises, we haven't seen anything concrete yet. A case in point, for example, was that Mr. Trump said precious little about tax cut and infrastructure at his press meeting last week.

In any case, the argument still goes something like this. The new U.S administration wants to mitigate the adverse impact on American workers from "free" trade. In short, it wants to make access to U.S. markets more difficult, and wants to create a tax/tariff regime that favours domestic production relative to producing abroad and re-exporting to the U.S. It also wants to inject significant fiscal stimulus via tax cuts and infrastructure spending. All this is supposed to happen at a point when the economy is close to full employment. Given the Fed's reaction function this creates a combination of loose fiscal policy, tight monetary policy spiced up with less free trade. In other words, an inflation bonfire, higher yields and by derivative a much stronger dollar. We can discuss whether this policy mix will in fact emerge, but if it does, I think betting on a stronger dollar is a fair bet.

One of the problems, though, is that that the details of the policies are quite complicated. Consider the case of the cross-border tax. We have no concrete details, but the policy appears to have two components. Firstly, the idea is to impose a VAT-like tax of 20% specifically on all imports, but not as far as I can understand on products and services produced domestically. The impetus for this policy proposal partly is to broaden the tax base and bring it in line with many of the U.S. "competitors" who have large indirect taxes, albeit on all products and services. A tax on imports, however, would also be an attempt to bring back production to U.S. shores, and to deter firms from producing abroad and re-exporting back into the U.S. The best example of this is Trump's apparent desire to rip up NAFTA. Indeed, the genesis of the policy partly appears to be what is perceived as unfair competition within the FTA from low-wage production in Mexico. After that comes China of course, but that fight will be entirely different one for Mr. Trump.

Secondly, the idea is the to exempt exports altogether from taxation. This would happen in two steps as far as I can see. Bring down down the overall corporate tax rate from 35% to 20%, and then apply an asymmetric offset of the 20% import tax on exports. In other words, the idea is to make income earned from exports essentially tax free. This has led commentators to predict all kinds of weird and wonderful shifts in the make-up of U.S. trade; essentially an export boom. But this is highly unlikely. Just because you decide to tax imports, and exempt exports from taxation, doesn't mean that firms can suddenly decide to shift their trading behavior. In fact, economic theory is pretty clear on this point. Tax regimes don't affect the size of a country's trade sector. To confirm this point I ran a small cross-sectional study using the World Bank database. Firstly, I tried to predict openness—the sum of imports and exports as % of GDP—as a function of tax on goods and services, and second I used imports as % of GDP as the dependent variable. As you can see, the fruit of my labour was one big zero, exactly what we should expect.

Openness does not appear to react to indirect taxes ...

…and neither does imports

This is not to say, though, that the impact of such policies would be trivial, but it isn't easy for investors to gauge what their effect will be. Consider for example the conflicting explanations by heavy-weight economists Adam Posen and Martin Feldstein last week in their respective interviews on Bloomberg TV. Are you confused yet?

When economists analyse the impact on a country's trade behaviour from a change in tax regime, they usually assume that economy is "small." This means that they assume the country's behaviour does not affect world prices. Clearly, this is not the case with the U.S. economy and suggests that an aggressive U.S. border-adjustment tax would send ripples around the world in terms of policies and trade flows. The counterargument to this, though, is exactly included in the dollar-bull story. After all, if the dollar appreciates by 20% in response to a change in tax rates such as suggested above, the trade-effect of the policy should be nullified. Adding it all together I think we are looking at three central scenarios for this story.

1) Raging USD bull, higher global growth. In this scenario, Mr. Trump's policy mix emphasises domestic fiscal stimulus, but a relatively benign clampdown on free trade if any at all. The Fed raises rates, but the U.S. economy continues to power ahead by sucking in savings from abroad. The USD appreciates, the U.S. c/a deficit widens, and we all live happily ever after, at least for a while.

2) Stronger USD offsets aggressive border adjustment tax. In this scenario, the border tax adjustment happens, but a stronger dollar offsets the impact on the U.S. trade deficit. The key changes in this scenario would be within the U.S. economy and the economies of its closest trading partners.

3) Weaker USD with an aggressive border adjustment tax. In this scenario, Mr. Trump goes full retard on the border adjustment tax/free trade clampdown. The USD dollar depreciates because markets perceive it to be adverse to U.S. economic growth. Domestic inflation rises sharply, the U.S. economy slows and the trade deficit narrows. The rest of the world is pulled down with the U.S. economy and a global recession ensues.

The bad news is that it isn't easy to see exactly where we go from here. My bet is on a halfway house between 1) and 2). I am not delusional enough to believe in a clean number 1) as it seems many investors are hoping for. The good news, though, is that we're about to find out. After all, reality has a tendency to catch up with even the strongest narrative.

The portfolio

I have finally come around to updating this. Some changes have been made since I did it. I have taken profit on my long in Japanese equities, and added two small cap U.K. healthcare providers. I am sniffing around for opportunities in this sector elsewhere too. I have also added two very minor positions in AIM single names, as well as I have added to my FTSE short. Overall, the portfolio seems to have re-discovered its mojo slightly at the start of the year, but it is still trailing the MSCI World. In other words, I can't quite say whether the latest adjustments have anything resembling "alpha" about them.